Antarctic krill

| Antarctic krill | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Euphausiacea |

| Family: | Euphausiidae |

| Genus: | Euphausia |

| Species: | E. superba |

| Binomial name | |

| Euphausia superba Dana, 1850 |

|

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. Antarctic krill are shrimp-like invertebrates or crustaceans that live in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic meter.[1] They feed directly on minute phytoplankton, thereby using the primary production energy that the phytoplankton originally derived from the sun in order to sustain their pelagic (open ocean) life cycle.[2] They grow to a length of 6 cm (2.4 in), weigh up to 2 g (0.7 oz), and can live for up to six years. They are a key species in the Antarctic ecosystem and are, in terms of biomass, probably the most successful animal species on the planet (approximately 500 million tonnes).[3]

Contents |

Systematics

All members of the krill order are shrimp-like animals of the crustacean superorder Eucarida. Their breastplate units, or thoracomers, are joined with the carapace. The short length of these thoracomers on each side of the carapace makes the gills of Antarctic krill visible to the human eye. The legs do not form a jaw structure, which differentiates this order from the crabs, lobsters and shrimp.

Life cycle

The main spawning season of Antarctic krill is from January to March, both above the continental shelf and also in the upper region of deep sea oceanic areas. In the typical way of all euphausiaceans, the male attaches a sperm package to the genital opening of the female. For this purpose, the first pleopods (legs attached to the abdomen) of the male are constructed as mating tools. Females lay 6,000–10,000 eggs at one time. They are fertilized as they pass out of the genital opening by sperm liberated from spermatophores which have been attached by the males.[4]

According to the classical hypothesis of Marr,[5] derived from the results of the expedition of the famous British research vessel RRS Discovery, egg development then proceeds as follows: gastrulation (development of egg into embryo) sets in during the descent of the 0.6 mm eggs on the shelf at the bottom, in oceanic areas in depths around 2,000–3,000 m. From the time the egg hatches, the 1st nauplius (i.e., larval stage) starts migrating towards the surface with the aid of its three pairs of legs; the so-called developmental ascent.

The next two larval stages, termed 2nd nauplius and metanauplius, still do not eat but are nourished by the remaining yolk. After three weeks, the little krill has finished the ascent. They can appear in enormous numbers counting 2 per liter in 60 m water depth. Growing larger, additional larval stages follow (2nd and 3rd calyptopis, 1st to 6th furcilia). They are characterized by increasing development of the additional legs, the compound eyes and the setae (bristles). At 15 mm, the juvenile krill resembles the habitus of the adults. Krill reach maturity after two to three years. Like all crustaceans, krill must molt in order to grow. Approximately every 13 to 20 days, krill shed their chitinous exoskeleton and leave it behind as exuvia.

Food

The gut of E. superba can often be seen shining green through the animal's transparent skin, an indication that this species feeds predominantly on phytoplankton—especially very small diatoms (20 μm), which it filters from the water with a feeding basket.[6] The glass-like shells of the diatoms are cracked in the "gastric mill" and then digested in the hepatopancreas. The krill can also catch and eat copepods, amphipods and other small zooplankton. The gut forms a straight tube; its digestive efficiency is not very high and therefore a lot of carbon is still present in the feces (see "the biological pump" below).

In aquaria, krill have been observed to eat each other. When they are not fed in aquaria, they shrink in size after molting, which is exceptional for animals the size of krill. It is likely that this is an adaptation to the seasonality of their food supply, which is limited in the dark winter months under the ice. However, the animal's compound eyes do not shrink, and so the ratio between eye size and body length has thus been found to be a reliable indicator of starvation.[7]

Filter feeding

Antarctic krill directly utilize the minute phytoplankton cells, which no other animal of krill size can do. This is accomplished through filter feeding, using the krill's highly developed front legs, providing for an efficient filtering apparatus:[8] the six thoracopods (legs attached to the thorax) form a very effective "feeding basket" used to collect phytoplankton from the open water. In the finest areas the openings in this basket are only 1 μm in diameter. In the movie linked to the left, the krill is hovering at a 55° angle on the spot. In lower food concentrations, the feeding basket is pushed through the water for over half a meter in an opened position, as in the in situ image below, and then the algae are combed to the mouth opening with special setae (bristles) on the inner side of the thoracopods.

Ice-algae raking

Antarctic krill can scrape off the green lawn of ice-algae from the underside of the pack ice.[9][10] The image to the right, taken via a ROV,[11] shows how most krill swim in an upside-down position directly under the ice. Only a single animal (in the middle) can be seen hovering in the free water. Krill have developed special rows of rake-like setae at the tips of the thoracopods, and graze the ice in a zig-zag fashion, akin to a lawnmower. One krill can clear an area of a square foot in about 10 minutes (1.5 cm²/s). It is relatively new knowledge that the film of ice algae is very well developed over vast areas, often containing much more carbon than the whole water column below. Krill find an extensive energy source here, especially in the spring.

Biological pump and carbon sequestration

Krill are thought to undergo between one and three vertcal migrations from mixed surface waters to depth each day.[12] The krill is a very untidy feeder, and it often spits out aggregates of phytoplankton (spit balls) containing thousands of cells sticking together. It also produces fecal strings that still contain significant amounts of carbon and the glass shells of the diatoms. Both are heavy and sink very fast into the abyss. This process is called the biological pump. As the waters around Antarctica are very deep (2,000–4,000 m), they act as a carbon dioxide sink: this process exports large quantities of carbon (fixed carbon dioxide, CO2) from the biosphere and sequesters it for about 1,000 years.

If the phytoplankton is consumed by other components of the pelagic ecosystem, most of the carbon remains in the upper strata. There is speculation that this process is one of the largest biofeedback mechanisms of the planet, maybe the most sizable of all, driven by a gigantic biomass. Still more research is needed to quantify the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

Biology

Bioluminescence

Krill are often referred to as light-shrimp because they can emit light, produced by bioluminescent organs. These organs are located on various parts of the individual krill's body: one pair of organs at the eyestalk (cf. the image of the head above), another pair on the hips of the 2nd and 7th thoracopods, and singular organs on the four pleonsternites. These light organs emit a yellow-green light periodically, for up to 2 to 3 seconds. They are considered so highly developed that they can be compared with a torchlight: a concave reflector in the back of the organ and a lens in the front guide the light produced, and the whole organ can be rotated by muscles. The function of these lights is not yet fully understood; some hypotheses have suggested they serve to compensate the krill's shadow so that they are not visible to predators from below; other speculations maintain that they play a significant role in mating or schooling at night.

The krill's bioluminescent organs contain several fluorescent substances. The major component has a maximum fluorescence at an excitation of 355 nm and emission of 510 nm.[13]

Escape reaction

Krill use an escape reaction to evade predators, swimming backwards very quickly by flipping their rear ends This swimming pattern is also known as lobstering. Krill can reach speeds of over 60 cm/s.[14] The trigger time to optical stimulus is, despite the low temperatures, only 55 ms.

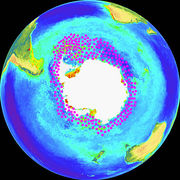

Geographical distribution

Antarctic krill are found thronging the surface waters of the Southern Ocean; they have a circumpolar distribution, with the highest concentrations located in the Atlantic sector.

The northern boundary of the Southern Ocean with its Atlantic, Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean sectors is defined more or less by the Antarctic convergence, a circumpolar front where the cold Antarctic surface water submerges below the warmer subantarctic waters. This front runs roughly at 55° South; from there to the continent, the Southern Ocean covers 32 million square kilometers. This is 65 times the size of the North Sea. In the winter season, more than three quarters of this area become covered by ice, whereas 24 million square kilometers become ice free in summer. The water temperatures range between −1.3 and 3 °C.

The waters of the Southern Ocean form a system of currents. Whenever there is a West Wind Drift, the surface strata travels around Antarctica in an easterly direction. Near the continent, the East Wind Drift runs counterclockwise. At the front between both, large eddies develop, for example, in the Weddell Sea. The krill schools drift with these water masses, to establish one single stock all around Antarctica, with gene exchange over the whole area. Currently, there is little knowledge of the precise migration patterns since individual krill cannot yet be tagged to track their movements.

Ecology

Antarctic krill is the keystone species of the Antarctica ecosystem, and provides an important food source for whales, seals, Leopard Seals, fur seals, Crabeater Seals, squid, icefish, penguins, albatrosses and many other species of birds. Crabeater seals have even developed special teeth as an adaptation to catch this abundant food source: its most unusual multilobed teeth enable this species to sieve krill from the water. Its dentition looks like a perfect strainer, but how it operates in detail is still unknown. Crabeaters are the most abundant seal in the world; 98% of their diet is made up of E. superba. These seals consume over 63 million tonnes of krill each year.[15] Leopard seals have developed similar teeth (45% krill in diet). All seals consume 63–130 million tonnes, all whales 34–43 million tonnes, birds 15–20 million tonnes, squid 30–100 million tonnes, and fish 10–20 million tonnes, adding up to 152–313 million tonnes of krill consumption each year.[16]

The size step between krill and its prey is unusually large: generally it takes three or four steps from the 20 μm small phytoplankton cells to a krill-sized organism (via small copepods, large copepods, mysids to 5 cm fish).[2] The next size step in the food chain to the whales is also enormous, a phenomenon only found in the Antarctic ecosystem. E. superba lives only in the Southern Ocean. In the North Atlantic, Meganyctiphanes norvegica and in the Pacific, Euphausia pacifica are the dominant species.

Biomass and production

The biomass of Antarctic krill is estimated to be between 125 to 725 million tonnes,[17] arguably making E. superba the most successful animal species on the planet. It should be noted that of all animals visible to the naked eye some biologists speculate that ants provide the largest biomass (but this speculation adds up hundreds of different species) whilst others speculate that it could be the copepods, but this too would be the sum of many hundreds of species that exist over the planet. To get an impression of the biomass of E. superba against that of other species: The total non-krill yield from all world fisheries, finfish, shellfish, cephalopods and plankton is about 100 million tonnes per year whilst estimates of the Antarctic krill production are between 13 million to several billion tonnes per year.

The reason Antarctic krill are able to build up such a high biomass and production is that the waters around the icy Antarctic continent harbor one of the largest plankton assemblages in the world, possibly the largest. The ocean is filled with phytoplankton; as the water rises from the depths to the light-flooded surface, it brings nutrients from all of the world's oceans back into the photic zone where they are once again available to living organisms.

Thus primary production—the conversion of sunlight into organic biomass, the foundation of the food chain—has an annual carbon fixation of between 1 and 2 g/m² in the open ocean. Close to the ice it can reach 30–50 g/m². These values are not outstandingly high, compared to very productive areas like the North Sea or upwelling regions, but the area over which it takes place is enormous, even compared to other large primary producers such as rainforests. In addition, during the Austral summer there are many hours of daylight to fuel the process. All of these factors make the plankton and the krill a critical part of the planet's ecocycle.

Decline with shrinking pack ice

There are concerns that the overall biomass of Antarctic krill has been declining rapidly over the last few decades. Some scientists have speculated this value being as high as 80% in the last 30 years. This could be caused by the reduction of the pack ice zone due to global warming.[19] The graph on the right depicts the rising temperatures of the Southern Ocean and the loss of pack ice (on an inverted scale) over the last years 40 years. Antarctic krill, especially in the early stages of development, seem to need the pack ice structures in order to have a fair chance of survival. The pack ice provides natural cave-like features which the krill uses to evade their predators. In the years of low pack ice conditions the krill tend to give way to salps,[20] a barrel-shaped free-floating filter feeder that also grazes on plankton.

Ocean acidification

Another challenge for Antarctic krill, as well as many calcifying organisms (corals, bivalve mussels, snails etc.), is the Acidification of the oceans caused by increasing levels of carbon dioxide.[21] Krill exoskeleton contains carbonate, which is susceptible to dissolution under low pH conditions. Little is currently known about the effects that ocean acidification could have on the krill but scientists fear that it could significantly impact on its distribution, abundance and survival.[22][23]

Fisheries

The fishery of Antarctic krill is on the order of 100,000 tonnes per year. The major catching nations are South Korea, Norway, Japan and Poland.[24] The products are used as animal food and fish bait. Krill fisheries are difficult to operate in two important respects. First, a krill net needs to have very fine meshes, producing a very high drag, which generates a bow wave that deflects the krill to the sides. Second, fine meshes tend to clog very fast.

Yet another problem is bringing the krill catch on board. When the full net is hauled out of the water, the organisms compress each other, resulting in great loss of the krill's liquids. Experiments have been carried out to pump krill, while still in water, through a large tube on board. Special krill nets also are currently under development. The processing of the krill must be very rapid since the catch deteriorates within several hours. Its high protein and vitamin content makes krill quite suitable for both direct human consumption and the animal-feed industry.[25]

Future visions and ocean engineering

Despite the lack of knowledge available about the whole Antarctic ecosystem, large scale experiments involving krill are already being performed to increase carbon sequestration: in vast areas of the Southern Ocean there are plenty of nutrients, but still, the phytoplankton does not grow much. These areas are termed HNLC (high nutrient, low carbon). The phenomenon is called the Antarctic Paradox, and occurs because iron is missing.[26] Relatively small injections of iron from research vessels trigger very large blooms, covering many miles. The hope is that such large scale exercises will draw down carbon dioxide as compensation for the burning of fossil fuels.[27] Krill is the key player in this process, collecting the minute plankton cells which fix carbon dioxide and converting the substance to rapidly sinking carbon in the form of spit balls and fecal strings.

References

- ↑ Hamner, W. M., Hamner, P. P., Strand, S. W., Gilmer, R. W. (1983). "Behavior of Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba: Chemoreception, Feeding, Schooling and Molting'". Science 220 (4595): 433–435. doi:10.1126/science.220.4595.433. PMID 17831417.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kils, U., Klages, N (1979). "Der Krill". Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau 10: 397–402.

- ↑ Nicol, S., Endo, Y. (1997). Fisheries Technical Paper 367: Krill Fisheries of the World. FAO. http://www.fao.org/documents/show_cdr.asp?url_file=//DOCREP/003/W5911E/w5911e00.htm.

- ↑ Ross, R. M., Quetin, L. B. (1986). "How Productive are Antarctic Krill?". Bioscience 36 (4): 264–269. doi:10.2307/1310217. http://jstor.org/stable/1310217.

- ↑ Marr, J. W. S. (1962). "The natural history and geography of the Antarctic Krill Euphausia superba". Discovery report 32: 33–464.

- ↑ Ecoscope.Com

- ↑ Hyoung-Chul Shin, Nicol, S. (2002). "Using the relationship between eye diameter and body length to detect the effects of long-term starvation on Antarctic krill Euphausia superba". Marine Ecology Progress Series (MEPS) 239: 157–167. doi:10.3354/meps239157. http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v239/p157-167/.

- ↑ Kils, U.. Swimming and feeding of Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba - some outstanding energetics and dynamics - some unique morphological details. http://wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Uwe_Kils/polar/part1. In 'Editor: S. B. Schnack (1983). "On the biology of Krill Euphausia superba". Proceedings of the Seminar and Report of Krill Ecology Group (Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research,) Special Issue 4: 130–155 and title page image.

- ↑ Ecoscope.Com

- ↑ Marschall, P. (1988). "The overwintering strategy of Antarctic krill under the pack ice of the Weddell Sea". Polar Biology 9: 129–135. doi:10.1007/BF00442041.

- ↑ Kils, U., Marshall, P.. Der Krill, wie er schwimmt und frisst - neue Einsichten mit neuen Methoden ("Antarctic krill - feeding and swimming performances - new insights with new methods"). pp. 201–210. In Hempel, I., Hempel, G. (1995). Biologie der Polarmeere — Erlebnisse und Ergebnisse (Biology of the polar oceans). Fischer. ISBN 3-334-60950-2.

- ↑ Geraint A. Tarling & Magnus L. Johnson (2006). "Satiation gives krill that sinking feeling". Current Biology 16 (3): 83–84. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.044. PMID 16461267.

- ↑ Harvey, H. R., Se-Jong Ju (2001). Biochemical Determination of Age Structure and Diet History of the Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba, during Austral Winter. Third U.S. Southern Ocean GLOBEC Science Investigator Meeting, Arlington. http://www.ccpo.odu.edu/Research/globec/3sciinvest/harvey.htm.

- ↑ Kils, U. (1982). "Swimming Behaviour, Swimming Performance and Energy Balance of Antarctic Krill Euphausia superba". BIOMASS Scientific Series. BIOMASS Research Series 3: 1–122. http://www.ecoscope.com/biomass3.htm.

- ↑ Bonner, B.. Birds and Mammals — Antarctic Seals. pp. 202–222. In Buckley, R. (1995). Antarctica. Pergamon Press.

- ↑ Miller, D. G., Hampton, I. (1989). "Biology and Ecology of the Antarctic Krill (Euphausia superba Dana): a review". BIOMASS Scientific Series 9: 1–66.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Species Fact Sheet Euphausia superba". FAO. http://www.fao.org/figis/servlet/species?fid=3393. Retrieved June 16, 2005.

- ↑ Loeb, V., Siegel, V., Holm-Hansen, O., Hewitt, R., Fraser, W., et al. (1997). "Effects of sea-ice extent and krill or salp dominance on the Antarctic food web". Nature 387: 897–900. doi:10.1038/43174.

- ↑ Gross, L. (2005). "As the Antarctic Ice Pack Recedes, a Fragile Ecosystem hangs in the Balance". PLoS Biology 3 (4): 127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030127. PMID 15819605.

- ↑ Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E., Rothery, P. (2004). "Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean". Nature 432 (7013): 100–103. doi:10.1038/nature02996. PMID 15525989.

- ↑ ACE CRC (2008). Position analysis: CO2 emissions and climate change: OCEAN impacts and adaptation issues.

- ↑ The Australian (2008). Swiss marine researcher moving in for the krill. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24392216-27703,00.html.

- ↑ Orr, James C.; et al. (2005). "Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms". Nature 437 (7059): 681–686. doi:10.1038/nature04095. PMID 16193043.

- ↑ CCAMLR Statistical Bulletin vol. 20 (1998-2007), CCAMLR, Hobart, Australia, 2008. URL last accessed 2008-07-03. Note that the FAO (FIGIS) and the CCAMLR data are not identical, but generally agree on the order of 1'000 tonnes.

- ↑ Everson, I., Agnew D. J., Miller, D. G. M.. Krill fisheries and the future. pp. 345–348. In Everson, I. (ed.) (2000). Krill: biology, ecology and fisheries. Oxford, Blackwell Science.

- ↑ The Iron Hypothesis

- ↑ Climate Engineering

Further reading

- Clarke, A. (1983) Towards an energy budget for krill: The physiology and biochemistry of Euphausia superba Dana. Polar Biology 2(2)

- Hempel, I.; Hempel, G.: Field observations on the developmental ascent of larval Euphausia superba (Crustacea). Polar Biol 6; pp. 121 – 126; 1986.

- Hempel, G.: Antarctic marine food webs. In Siegfried, W. R.; Condy, P. R.; Laws, R. M. (eds): Antarctic nutrient cycles and food webs. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 266 – 270; 1985.

- Hempel, G.: The krill-dominated pelagic system of the Southern Ocean. Envir. Inter. 13, pp. 33 – 36; 1987.

- Hempel, G.: Life in the Antarctic sea ice zone. Polar Record 27(162); pp. 249 – 253; 1991

- Hempel, G.; Sherman, K.: Large marine ecosystems of the world: trends in exploitation, protection, and research. Elsevier, Amsterdam: Large marine ecosystems 12, 423 pp; 2003

- Ikeda, T. (1984) The influence of feeding on the metabolic activity of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba Dana). Polar Biology 3(1)

- Ishii, H. (1987) Metabolic rates and elemental composition of the Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba Dana. Polar Biology 7(6)

- Kils, U., (2006) So frisst der Krill [How krill feeds. In: Hempel, G., Hempel, I., Schiel, S., Faszination Meeresforschung, Ein oekologisches Lesebuch. Hauschild Bremen, 112–115

- Mauchline, J.; Fisher, L.R.: The biology of euphausiids. Adv. Mar. Biol. 7; 1969.

- Nicol, S. & de la Mare, W. K. Ecosystem management and the Antarctic krill. American Scientist 81 (No. 1), pp. 36–47. Biol 9:129–135; 1993.

- Nicol, S.; Foster, J.: Recent trends in the fishery for Antarctic krill, Aquat. Living Resour. 16, pp. 42 – 45; 2003.

- Quetin, L. B., Ross, R. M. and Clarke, A.: Krill energetics: seasonal and environmental aspects of the physiology of Euphausia superba. In El-Sayed, S. Z. (ed.): Southern Ocean Ecology: the BIOMASS perspective, pp. 165 – 184. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Sahrhage, D.: Antarctic Krill Fisheries: Potential Resources and Ecological Concerns. In Caddy, J. F. (ed.): Marine Invertebrate Fisheries; their assessment and management; pp. 13 – 33. Wiley, 1989.

External links

- Webcam of Krill Aquarium at Australian Antarctic Division

- 'Antarctic Krill fact sheet' from the Australian Antarctic Division

- Euphausia superba from MarineBio

- "Krill fights for survival as sea ice melts" from the NASA's "Earth Observatory".

- A time to krill

- Extensive bibliography.

- Krill Count Project

- Diary of the RRS James Clark Ross, giving a popular introduction to the Antarctic krill.

- "Climate row touches blue whales", from the BBC, July 19, 2001.

- "Virtual microscope" of Antarctic krill for an interactive tour of their morphology and behavior, along with other peer-reviewed information.

- "Antarctic Wildlife at Risk From Overfishing, Experts Say", from National Geographic News, August 5, 2003.